Poetry & Friendship

I think many of us dream of writing poetry when we are young. We try our hand at it a couple of times, amass pages in a notebook, and eventually find the courage to print out a few fledgling poems. Our heads bowed, we dare to show those poems to someone we admire, a teacher or a published writer. And when that person says our poems are awful, it’s a shot in the heart. Those who are strong will ignore the wound and keep on writing. Those plagued with self-doubt will stop writing and tell themselves they are unworthy of being called a poet.

I think many of us dream of writing poetry when we are young. We try our hand at it a couple of times, amass pages in a notebook, and eventually find the courage to print out a few fledgling poems. Our heads bowed, we dare to show those poems to someone we admire, a teacher or a published writer. And when that person says our poems are awful, it’s a shot in the heart. Those who are strong will ignore the wound and keep on writing. Those plagued with self-doubt will stop writing and tell themselves they are unworthy of being called a poet.

When told my poems weren’t good enough, I gave up. Years later, when I took up poetry again, I wrote an autobiographical poem about being an “Obedient Student.” I hope it will serve as a mantra to others not to follow in my path.

Obedient Student

I was such an obedient student that when my teachers told me I wouldn’t make a good poet, I stopped writing. I adored words more than anything else in the world and preferred to cut out my tongue than to insult the Muses with my sickly and impoverished language. That is why these poems are so timid: like the invalid who rises from her bed after a long convalescence and walks embracing the walls.

As a young woman I put away all thoughts of poetry and pursued a career in cultural anthropology. I traveled to Spain. I traveled to Mexico. I became a nomad and got to see a bit of the world. Maybe that wasn’t so bad, in the end. I learned to write in a different genre—ethnography—and told stories of the people in foreign places that took me into their lives like an orphan.

These journeys led me to think about the meaning of home and finally, in the early 1990s, I decided it was time to travel to Cuba, where I was born. My legs trembled as I traced steps I’d taken as a child, as I wandered through the park where I played under thick-rooted banyan trees. Like a ghost, I slipped in and out of apartments in the oldest parts of Havana, near the port and the sea, where my Jewish family lived.

These journeys led me to think about the meaning of home and finally, in the early 1990s, I decided it was time to travel to Cuba, where I was born. My legs trembled as I traced steps I’d taken as a child, as I wandered through the park where I played under thick-rooted banyan trees. Like a ghost, I slipped in and out of apartments in the oldest parts of Havana, near the port and the sea, where my Jewish family lived.

The experience was powerful and the uncertain poet within me longed to lift her voice. I feared the axe but still scribbled down a few lines. I kept going until I had a handful of poems. Who could I share them with? Who could tell me whether to keep going, or stop once and for all and let others write poems, not me?

I have come to believe all a poet needs is one friend in the world to find the faith to keep writing. Such a friend came into my life twenty years ago in Cuba. That friend is Rolando Estévez, a poet and artist and a maker of beautiful handmade books.

Estévez has a sad personal story of loss and abandonment. His parents and younger sister, who was eight at the time, immigrated to Miami from Cuba in 1969, and he, at the age of fifteen, was left under the supervision of his godparents, but mostly had to fend for himself. He couldn’t accompany his family because he was of military age and his father refused to tolerate another day in the communist system. When his mother came to visit him, ten years after leaving, she suffered a nervous breakdown on her return to Miami. He never saw his father again and decades passed before he and his sister were able to reunite. Through all this turmoil, it was art and poetry that kept him sane. When he discovered he could join art and poetry by making handmade books, the stars aligned. Channeling William Blake, he searched for the harmony between words and images.

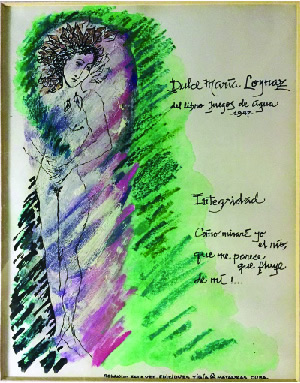

I met Estévez—who prefers to be called by his last name—at the Havana Book Fair in 1995. I was immediately drawn to a set of stunning illustrations he had made to pair up with poems by the Cuban poet, Dulce María Loynaz, whom I knew nothing about back then. “What, you haven’t heard of Dulce Maria?” He looked aghast. “You don’t know anything about Cuba if you don’t know her. She’s one of our greatest poets!” Thanks to Estévez, I studied Loynaz’s poetry and my life was changed. I found my muse, found inspiration. I was also fortunate to meet Loynaz and would visit her frequently in her ruined mansion in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana. She was very frail in the last years before she passed away but very alert and asked me to read poems aloud to her.

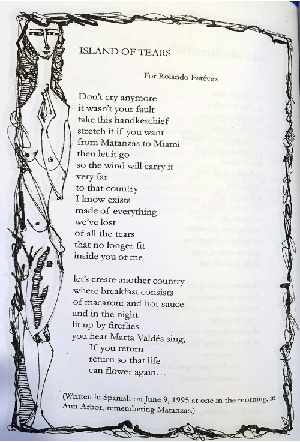

When I told Estévez I was writing poems, he said he wanted to read them. I told him they were in English and he smiled and said, “Well, you’ll have to write them in Spanish.” And so I began to write in English and Spanish, sometimes starting in one language or the other, depending on the words that came to me first. It was a joy to write in Spanish, my mother tongue, but all my schooling had been in English and I made grammatical mistakes. Estévez would correct me gently, in the process helping me to deepen my knowledge of Spanish. One of the first poems I originally wrote in Spanish was dedicated to Estévez and called “Island of Tears.”

When I told Estévez I was writing poems, he said he wanted to read them. I told him they were in English and he smiled and said, “Well, you’ll have to write them in Spanish.” And so I began to write in English and Spanish, sometimes starting in one language or the other, depending on the words that came to me first. It was a joy to write in Spanish, my mother tongue, but all my schooling had been in English and I made grammatical mistakes. Estévez would correct me gently, in the process helping me to deepen my knowledge of Spanish. One of the first poems I originally wrote in Spanish was dedicated to Estévez and called “Island of Tears.”

Estévez is a thorough and compassionate reader and that gives him the ability to create images that do more than illuminate what the words convey; they bring you to the edge of the unspeakable. He has many years of experience designing sets for a theater in Matanzas and the books he constructs often feel like elaborate arenas for a drama to unfold. But his books are also cozy homes for poems to relax in their pajamas and just be.

I am blessed that my poems are featured in beautiful handmade books that Estévez has created. Every design is different, unpredictable, thrilling. But it all begins with Estévez being willing to read each poem one at a time in a non-judgmental way. He’s never said a poem is unsalvageable. He’ll tell me if a poem has wings to fly, or if a poem still needs a little more cuddling. Lately he says my Spanish has improved so much there are hardly any mistakes to correct. Now I take it for granted that I’ll write every poem in English and Spanish.

But I’ll never take my friendship with Estévez for granted. I treasure it like a ruby. As long as he sees the poet in me, I think I can see the poet in me too.

Ruth Behar on the influence of Dulce María Loynaz on her writing as an anthropologist.