With Felicia and Edmundo in Israel

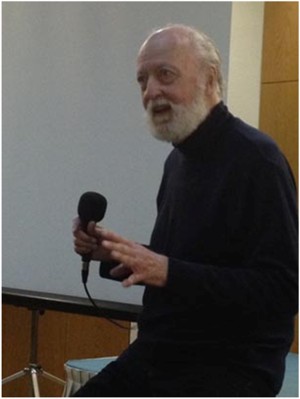

Edmundo Desnoes

I knew who they were the minute I saw them at JFK Airport. He was tall, white-haired and white-bearded, elegant in a black turtleneck, and she was slender and sleek and had a well-traveled air about her. They were no longer young but you could never call them old. He stood too straight and she looked out at the world with too much curiosity. Later I learned they were both 82.

“Felicia? Edmundo?” I asked.

She turned to me with a smile. “Yes, it’s us.”

Felicia Rosshandler is the author of Passing Through Havana, an autobiographical novel about her German-Jewish family’s escape to Cuba at the time of the Holocaust and her unceasing search for home.

Edmundo Desnoes is the author of the novella, Memorias inconsolables(Inconsolable Memories), which later inspired the screenplay for the 1967 film, Memorias del subdesarrollo (Memories of Underdevelopment), directed by Tomás Gutierrez Alea, one of Cuba’s greatest filmmakers.

I had admired them from afar for many years. I never thought I’d get to meet them. It took a conference in Jerusalem on the topic of “Cuba—Myth and Reality” for me to cross paths with Felicia and Edmundo.

On the plane they sat a few rows ahead in the Economy Comfort section. I fell asleep soon after take off. When we landed in Tel Aviv, we gathered our bags, went through customs, and found a taxi to take the three of us to Jerusalem. Our host, Margalit Bejarano, had given us an idea of what it would cost, but the driver said it was still Shabbat and they charged more for their services on the Jewish day of rest. We didn’t argue. Edmundo got in the front and I rode with Felicia in the back seat.

Neither Felicia nor Edmundo had ever traveled to Israel. Felicia pointed out the signs in Hebrew and Arabic, the towns we passed along the dry yellow roads. She tried to ask a few questions of the driver, but he was not the talkative sort. We reached the Hebrew University campus on Mount Scopus as the setting sun spread a dusty pink veil over Jerusalem on the last Saturday at the end of May.

Neither Felicia nor Edmundo had ever traveled to Israel. Felicia pointed out the signs in Hebrew and Arabic, the towns we passed along the dry yellow roads. She tried to ask a few questions of the driver, but he was not the talkative sort. We reached the Hebrew University campus on Mount Scopus as the setting sun spread a dusty pink veil over Jerusalem on the last Saturday at the end of May.

Over the next few days I got to see a lot of them at the conference. They were our respected celebrities, but acted humbly and were present at every panel. Only one afternoon did Felicia sneak out with me to have a look at Mamilla Avenue. We found our way to the Arab souk. We didn’t have much time, so we walked briskly and the merchants called out playfully to us to at least have a look at their wares. Felicia, I learned, collects thimbles. She came across a basket of them as we swept past and bought one for each of us. It was a beautiful gift, reminding me of how Baba, my maternal grandmother, wore one while hemming my skirts when I was a girl.

Our cab driver spun the car around in crazy circles trying to find our building on Mount Scopus, but we managed to return in time from our outing for Edmundo’s introduction to the screening of Memories of Underdevelopment. Edmundo said it was an old film that continues to strike a chord with young people. He’s right. Every year I teach a course on “Cuba and Its Diaspora” and I always show the film. My students identify with the complex feelings of the protagonist, Sergio, a man of the white middle class of Havana who chooses to stay in revolutionary Cuba even after his parents and wife and friends have left for Miami. He’s ambivalent about being a revolucionario and is an ironic observer of the changes taking place around him. The film begins at the time of the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and ends with the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, when the island is briefly and dangerously at the center of world politics. It seamlessly weaves together the life of one individual with history.

I know the film by heart, but watching it with Edmundo sitting right in front of me was very moving. At the end of the screening, I turned to congratulate him and we hugged each other. He was sweating. Even though he’s so celebrated an author, he’d been nervous to share this masterpiece with an audience in Israel, many of whom were seeing it for the first time.

An apartment block, Israel, 2013

Felicia was the inspiration for the Jewish girl who appears in the film, the one whom Sergio falls in love with at the age of fifteen, the one he describes as more thoughtful than the Cuban girls of the era. She was the one he should have married.

In real life, Felicia told me, she and Edmundo went their separate ways. They met again in their twilight years, after she’d raised three sons in a previous marriage, after he’d married three times. It was their destiny, she said, to be together in their youth and old age.

Later on in the conference, Felicia read from her stunning memoir, which will be published soon. She quoted the lyrics of Volver, a tango she loved as girl, which she described as “a river filtering the debris of my life.”

Sentir que un soplo la vida, que veinte años no es nada…

To feel the breath of life, that twenty years is nothing…

What is twenty years? What is time, after all, but the opportunity to reencounter those whom we loved before and fall in love again?

I saw in the relationship of Felicia and Edmundo such a striking harmony of Jewish and Cuban sensibilities. It was a blessing to travel to Israel with them. In a land that is so hungry for peace, I felt the beauty of their romance and it gave me hope.