Returning from Japan

Everyone wanted to know: Is this your first time?

Yes. My first time in Tokyo. First time in Japan. First time in Asia.

I’m the kind of traveler who likes to go to the same places over and over. I rarely go to places where I won’t be able to talk to people. I’ve made short trips to Turkey and Poland, the ancient homelands of my grandparents, and to Israel, where I have family ties. Mostly I travel to places where I can speak Spanish, my native tongue—Spain, Mexico, Argentina, and Cuba, the land of my childhood.

And yet Japan has held a special place in my own map of the world. I always hoped I’d get to travel to Japan so I could find a boy I knew in second grade. Shotaro is his name, and we were together in the “dumb class,” because both of us were foreign kids and didn’t speak English. He was the only boy from school I invited to my birthday party in second grade. He came outfitted like a little man, in a gray suit, white shirt, and maroon tie. I wore one of my old Cuban dresses that barely fit me. We both did well and got good at English, but we didn’t continue together in third grade. His family decided to return to Japan, whereas it had become clear to my family that there wasn’t going to be any return to Cuba.

That Shotaro had a country he could return to, while I did not, left me troubled. As a child, I didn’t understand the condition of our exile: Had we given up our country voluntarily or been expelled?

I had asked David Slater, a professor of anthropology at Sophia University in Tokyo, who invited me to give a lecture at his campus, to help me locate Shotaro. He warned me it was unlikely Shotaro would reappear. Japanese people, he said, weren’t into Facebook and things of that sort. He still kindly sent out messages on my behalf to a few Japanese social media sites. As predicted, there was no response.

But there was another reason for me to go to Japan: my nephew, Max, is taking a year off from college to learn Japanese and he’d been in Tokyo for eight months and no one had gone to visit him yet. My brother, Mori, who hates to travel, considered going with me, but changed his mind, and my sister-in-law, Bea, was waiting until her vacation in July to go. While proud of Max’s independence, Mori was a little sorry Bea had introduced their son to such a far away country in his youth, when he was too impressionable. “What if he decides to move to Japan after college?” Mori lamented. “I’ll never see him.”

On a Thursday at five in the afternoon, Max was waiting for me at Narita Airport. “Okay, we’re taking the train,” he said, and we were off, with my four suitcases, to catch the express Skyliner, and then the local Ginza line to my hotel near Roppongi. I travel heavy, but tried not to feel too guilty as people politely stepped around my bags to get on and off the train. One of my suitcases was stuffed with boxes of Velveeta macaroni and cheese mix, the one “goodie” that Max had requested from the other side of the world.

Not that Max was lacking for noodles in Tokyo. That same night he took me to one of his favorite “dipping noodle” restaurants in Shinjuku. We stepped off the train into streets aglitter with neon signs and bustling with people going out to dinner after work. The restaurant was full, but we got corner seats at a long table. Noodles came in one bowl and broth in another. Instructions were provided in English as to how to eat the noodles:

1. First, please taste a fragrance.

2. Second, ladle up mouthful Noodles.

3. And then dip a Noodles to soup.

4. When you swallow Noodles, please enjoy it’s feeling.

5. It is smart to eat Noodles in one gulp with a moderate noise. It is a Japan style.

Votive tablets at the Meiji Jingu shrine

Two days later, we visited the Meiji Jingu shrine and saw votive tablets hanging around the sacred tree. Visitors had bought the tablets for 500 yen a piece and penned prayers in a variety of languages. I noted down a few in English: “Find a job that I like in 2013.” “I hope to finally realize what I want to become in life.” “Wishing health and happiness for my family & a cool new job for me.” “Bless us with health, happiness and success for our future together as man and wife.” And this simple one in Spanish: “Amor en la vida” (A Life of Love). I hoped all these prayers would be fulfilled, the last most of all.

Afterward we walked through the park that surrounds the shrine and when we reached the cafeteria Max insisted I try the green tea ice cream. He doesn’t much care for it. He thought I’d like it, though. He was right, I did. The tartness, the leafiness, grew on me, but I have to say I was glad when I finally ate my way down to the sugar cone.

Afterward we walked through the park that surrounds the shrine and when we reached the cafeteria Max insisted I try the green tea ice cream. He doesn’t much care for it. He thought I’d like it, though. He was right, I did. The tartness, the leafiness, grew on me, but I have to say I was glad when I finally ate my way down to the sugar cone.

Max knows all the best ramen places in Tokyo, and next stop, after a longish subway ride, was Tsukemen Michi, near the Kameari JR Station. We joined the line outside the restaurant. As we drew closer to the front, we got to sit on little stools. We were asked to pay for our food in advance, inserting money into a slot machine and giving the coupons to the waitress, then told to wait a while longer. It was a mild spring day, warm in the sun, cool in the shade. Everyone said it was a pity I’d come to Tokyo after the cherry blossoms bloomed. I think I couldn’t have asked for more heart-opening beauty than that tranquil street, with serene grandmothers pedaling past us on bicycles.

Vadin Montalvo, owner of Bar Asere

Forty-five minutes later, we were ushered inside. No wonder there’d been a line. The restaurant consisted of just eight seats around a counter surrounding the stove, where the owner, also the chef, cooked and prepared everything. After poring cold water on the homemade soba noodles, he caressed them before relinquishing them to us in large bowls. The broth was like rich gravy that could cure any ills. You could taste the love in the noodles. Max ordered the regular size and I got the woman’s size, which came with a crème brulee. Max had never tried such a delicacy before and took an immediate liking to it. What a fine meal. The only people at the restaurant were Japanese, and I didn’t want to embarrass Max, but I had to express my appreciation. As we stood to leave, I spoke Japanese for the first time. “Arigato,” I whispered. The owner-chef, a muscular man with a white bandana wrapped around his head, responded with delight. “Arigato!” he chimed back loudly. And he said more things Max had to translate. He wished me a good day and thanked me for coming to his restaurant and bowed good-naturedly and told me to come back. I didn’t hesitate to say arigato again after that.

Before arriving in Tokyo, I’d come across an announcement for the Primer Festival de Rumba. Thanks to the lovely Linda Hayakawa, a librarian at the American School in Japan who led me by the hand, I was able to attend. It was a sensational concert, with talented Japanese musicians and dancers, as well as Cubans, of course. Even the shy and modest Japanese audience jumped up to join the conga line that cascaded around the room as the concert drew to a close.

With Ludwig Núñez and Julián Oscar Tapia at La Bodeguita

Afterward I chatted with Julian Oscar Tapia. He was dressed all in white and wore the red bracelet of Eleguá, the deity that opens and closes doors. He’d been initiated into Santería before arriving in Tokyo a year ago. He was already fluent in Japanese, sending money to Cuba to support his mother, and married to a Japanese flight attendant. A marvelous singer, I later heard him croon such new Cuban classics as “Gozando en La Habana,” accompanied by his group, Timba Son. They play once a month at La Bodeguita, a Cuban restaurant owned by a Japanese brother and sister who spent part of their childhood in Cuba. I hadn’t realized I was craving homemade plantain chips until I got a delicious plateful at La Bodeguita. This cozy restaurant is a few blocks from the Shimokitzawa subway stop, though without Max’s expert knowledge I’d never have gotten there. Max also helped me find Bar Asere in Roppongi, where all the cubanos hang out, tell jokes, dance, and catch up on the news from Cuba. It’s an upstairs niche owned by Vadin Montalvo, who’s been living in Tokyo for ten years and has fulfilled his dream of opening his own business.

French macaroons in the Shibuya subway stop

While delighted that the Japanese graciously accepted my “arigatos,” it was frustrating not being able to tell the saleswoman at the Shibuya subway stop, who wrapped up my French macaroons in a box, how grateful I was that she’d gone to the trouble to make my package so pretty. Speaking Spanish to fellow Cubans in Tokyo, I was no longer the inarticulate child, and yet I felt coddled hearing the familiar words and rhythms I learned as a little girl. I couldn’t help notice that these Afrocuban men were prospering in ways that were impossible on our island, where it is unacceptable to be black and speak of racism. Like all Cubans, they were managing to hold on to our caffeinated exuberance while navigating through life on such a distant shore—on the quite different island of Japan.

Isaac at the American Club in Tokyo

If it’s a cliché that Cubans are now everywhere, they follow in the footsteps of the Jews, who have a long tradition of being part of far-flung diasporas all over the world. There are Jews in Tokyo and I had the good fortune to meet a few members of the community. My introduction came via Noriko Murai, an art historian at Sophia University who is a Japanese convert to Judaism. She’s married to Bill Yeskel, an American secular Jew, and they’re raising their four-year-old son, Isaac, to be a Jew in Japan—“Jubanese” and generous of spirit. When Isaac learned that my son, Gabriel, loved playing with Pokémon cards when he was a child, he pulled one out from his precious collection and said, “Give this to your son. I bet he doesn’t have a Pokémon card in Japanese.”

Haggadah in Hebrew, English, and Japanese

Jews have been living in Japan since the 1860s. In Tokyo, the Jewish Community of Japan was formally established in 1953. The center for prayer and social life is housed in a modern building in Shibuya with a quiet façade of interlocking Jewish stars. Designed by the Japanese architect, Fumihiko Maki, the building radiates calm, bringing together a mix of Jewish expatriates from the United States and Canada, who have lived in Tokyo for many years, and Japanese who are Jews by choice. Rabbi Antonio Di Gesu, who blogs under the name “gefilte sushi: a rabbi in Japan,” is the community’s rabbi. Born in Italy, he too is a Jew by choice and a sprightly man of great learning and multicultural wisdom. I was delighted when he ended Shabbat services by leading the singing of Ein Keloheinu in Ladino, the Old Spanish of the Sephardic Jews, just the way they do at the Cuban Sephardic temples in Havana and Miami.

I stayed after services for a lunch that featured some of the wonderful recipes from the cookbook, Fifty Years of Jewish Cooking in Japan. The fig newton style fruit cookies were addictive. Then there was a discussion with the book club about my book, An Island Called Home, that tells the story of my return journey to find the Jews of Cuba.

Ruth and Max at the Jewish Community of Japan

On the way back to the hotel, around the corner from my own favorite ramen restaurant, that I had actually introduced to Max, I thought I saw a sign that said Tango Rex. I suspected I was hallucinating. I’d brought along my tango shoes, which I’d long since packed away in my suitcase, not expecting to dance in Tokyo. I went online and found the website. The information was in Japanese. The cordial receptionists at the hotel, with whom I’d been exchanging bows for the past ten days, offered to call for me. Sure enough, there was a milonga that night, my last night in Tokyo. I had achy feet from walking all over the city, and it was cold and rainy. Should I go or not go? I stopped thinking and changed into a skirt with a bit of bounce, bundled up with a sweater under my coat, and walked over in sneakers.

The dance hall was so close, and I hadn’t known it was there. I burst in, my umbrella sopping wet. At the entrance stood Ricardo Cerqueiro, the director of this center for “Argentine tango dance and arts.” Though I looked far from glamorous, he welcomed me and was delighted I spoke Spanish. After I’d changed into my stilettos, he told me about the ups and downs of his life as a tango dancer in Tokyo, where he’s been for the last twelve years, and how there were many places he might have ended up, Chicago, or back in Buenos Aires, or Paris, but life had taken him to Tokyo, and he intended to stay. Finally, he asked me to dance and I was thrilled. He had the beautiful trusting embrace of the best of the milongueros. And yet I know I danced terribly. I was late on a few leads and stumbled. But he is more Japanese now than Argentine, so he was very polite, in the way the Japanese are, and put up with me longer than a porteño would have.

Much later that night the Japanese DJ played, “Ahora no me conoces,” (Now You Don’t Know Me), a melancholy tango from the 1940s, which you hear often at the milongas.

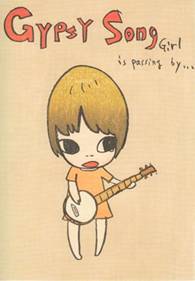

Yoshitomo Nara, “Gypsy Song” (2010)

Te perdiste del rincón natal

tras un sueño de distancia

sin pensar que allá quedaban

los seres que te amaban

y yo con mi constancia…

You wandered away

from the place where you were born

dreaming of being at a distance

never thinking that you left behind

the people who loved you

and me in all my steadfastness…

I thought about the wanderers I’d met in Tokyo, who have found a home in this humane city of clean subways and people with the most exquisite manners, and yet still sing the songs and dance the dances of their abandoned homes.

The next day Max took me to the airport, with my four suitcases again, the one with the Velveeta mac and cheese now filled with Japanese rice crackers wrapped in seaweed and dried yuzu fruit given to me by another lovely librarian, Kirby Yoshi.

I said goodbye to Max and to Japan, planning to return one day.

I feel so blessed to have visited the country where Shotaro was from. For a little while, he was, like me, an immigrant kid who carried around the grown-up sadness of a Yoshitomo Nara child. We spent a year together in the “dumb class,” and that’s not easy to forget, so if you happen to know a Shotaro who went to P.S. 117 in Queens, New York in 1963, could you let me know? By my next trip, maybe I’ll find him. I haven’t lost hope.